I'm Sorry, But Beauty Is Not in the Eye of the Beholder

An exploration into the degradation of city architecture, part two

It’s been longer than I had originally hoped for this follow-up article to my first writing on the degradation of city architecture, but I have not wasted all that time. Rather, I feel like I’ve been on a nearly unhinged intellectual journey that has taken me from modern economics to ancient cosmogony. Sometimes I feel like I’ve hit the bottom of it all, only to discover cavernous passageways beneath beckoning to me, dimly lit, hidden, and labyrinth in form.

I will try to synthesize that journey for you here in a series of posts, and perhaps this will be the end of my writing on it. Or maybe this discussion will find its way into other subjects — as I suspect it may be likely to do — since many of these ideas have implications for seemingly far-reaching topics.

But for now, we will start at the beginning. Why is this happening? How have we — the human race — gone from building some of the most magnificent buildings in the world to erecting structures that gridlock us in brutal ugliness, despite the unprecedented wealth generation and technological advancement we have at our fingertips?

To answer that, we must first step back and ask ourselves a more pointed question. Namely, is it just a matter of opinion?

Is beauty in the eye of the beholder?

The observation that I’ve made above — that we’ve slowly slid from awesome to awful architecture — is not even considered a valid point by many today, as architecture must be, it is said, a matter of personal opinion.

Common sense, or better yet — common feeling— begs to differ.

I mean this literally, and rather than try to convince you intellectually, which often leads to endless tail-chasing, I’m going to show you the example that most quickly convinced me of the point.

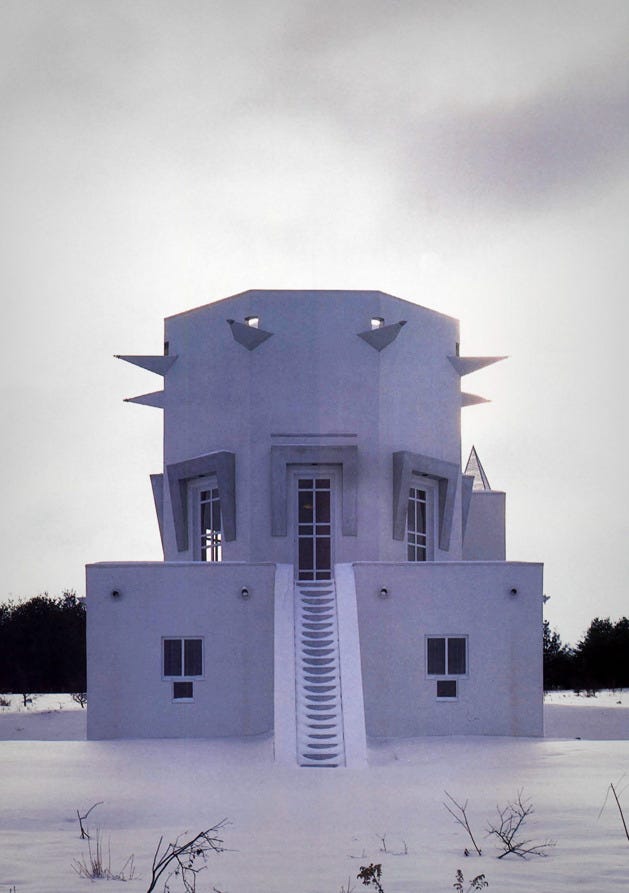

Take the below photos, the first a slum in Thailand and the second a postmodern house designed by architect Warren Schwartz. When looking at the pictures, ask yourself: Which one of these has more life?

If you answered the slum, you would be in league with pretty much everyone. If you answered the post-modern house, well…

I don’t believe you. And I doubt you do, either.

This is an example that famous architect and professor Christopher Alexander makes in his book The Nature of Order. (A different photo of a slum was used, but I believe the one presented here to be a close enough approximation for the point to carry.) In the book, he deliberately asks the reader to consider the “life” of the places presented, rather than the “beauty,” to clear the disorienting fog of perfectionism and stylization that the latter word often carries in Western culture. In so doing, he cuts to the heart of the matter. While Alexander does go into painstaking detail to define the term “life,” intuitively, we all know what he means by it. And, more importantly, we all prefer the things that are more life-giving (and hence beautiful), to those that aren’t. Even when comparing a slum to a designer’s house.1

The point can be made over and over again with different examples. A modern grocery store vs. a cathedral. A prison cell vs. an English cottage.

You might argue that of course a cathedral is more beautiful than a modern grocery store because the purposes of the two buildings are different.

That is true… and is also not the point.

Rather, the point is this: when presented with a pair of contrasting examples, you can and do determine one as more beautiful than the other, and, overwhelmingly, people agree about which one that is. Alexander literally tested the question. No one answered the post-modern house. Not even his architectural students who had been taught that the post-modern house was better.2

That point alone is fascinating. There is more agreement on what beauty is, when people see it rather than intellectualize about it, than there is disagreement. An agreed-upon hierarchy of beauty exists.

Even so, that doesn’t mean the road to determining what is truly beautiful is smooth sailing. Many factors may complicate the conversation. Cultural conditioning is one such factor.

For Alexander’s architectural students, as aforementioned, no one said the post-modern house had more life, but a few would invariably refuse to answer the question. After having further conversations with those students, Alexander interpreted this refusal as thus: they could not square what they were being taught in architecture school — that the post-modern house is to be admired — with what they knew, in their bones, to be true. So, they dismissed the question altogether.3

Intellectualism can often steer us away from our real feelings about things.

That said, the extreme examples can be used to remind us that we do, indeed, share a common feeling for things.

This should be encouraging to us (as well as a little uncomfortable considering our current cultural worldview). There is an objective standard of beauty, made obvious by the immense, collective agreement of people across time and culture when confronted with it in actuality. It may be hard to discern in less extreme examples, and Alexander makes a case for how we might do so in his 4 volumes The Nature of Order, but the fact of the matter remains: beauty actually exists. It is real. It’s not something left entirely up to individual preference.

This does not mean that one style of architecture is necessarily more beautiful than another. Many classic Buddhist temples and Islamic palaces are considered beautiful by the vast majority of diverse populaces, even though they are clearly not the same style. The tourism to these places is proof enough. Thus, there is great diversity in beauty, but beauty does have underlying patterns and principles.

If you’re interested in investigating what those patterns and principles might be, I encourage you to check out Alexander’s works, specifically The Timeless Way of Building, A Pattern Language, and his last great set: The Nature of Order.

For the many of us who have been baptized by birth into the modern way of thinking, the statement that beauty is objective may be hard to swallow, as its implications can strike the very core of our modern-day belief systems. It can shake up everything if you think about it for too long. But when we do consider it deeply, we find that this statement is indeed true, not because someone else claims it to be so, but because it resonates in every part of our being.

This realization is only a catapult into further questions, of course. If beauty is objective, then we can confidently say that, by and large, much of the older, more ancient architecture is more life-giving, more beautiful than our modern architecture. (Honestly compare the underlying structure of a modern suburban neighborhood to a well-preserved Medieval village if you’d like to argue.) If our predecessors knew how to produce better, more beautiful architecture: why and how? Why did they build as they did? What were they doing? How did these beautiful places come into being?

To answer these questions, we must attempt to get out of our own heads for a little bit, to strip away our modern and post-modern thought, to go back to pre-Enlightenment thinking.

For this, I turn once again to the works of our aforementioned architect, Christopher Alexander; a Catholic PhD Theology Lecturer, Mario Baghos; and the psychiatrist, neuroscience researcher, and philosopher, Iain McGilchrist.

Now, we will truly begin our descent into the labyrinth.

Christopher Alexander, The Nature of Order: The Phenomenon of Life (Berkley: The Center for Environmental Structure, 2002), 73.

Ibid., 74.

Ibid., 74

Another good article! The test of asking "which place has more life" is a brilliant way to short circuit our academic thinking. Alexander, Baghos, and McGuilquist are quite the power trio, excited to read the next one!

Thought provoking! I don't think it's a coincidence that as modern architecture has become more bland, boxy and vanilla, so too has culture with globalization, identity politics and even dress. While an obvious explanation might be that boxy buildings are quick, easy and cheap to build, they also have a demoralizing affect on people. I don't think people have fully considered the extent that architecture influences culture, and how our ugly, boxy towns and cities have dissolved community and contribute toward what often feels like a dystopia.