There's a reason ancient cities fill us with awe. And — surprise! — it's not efficiency.

Ancient people often built magnificently beautiful cities — because they approached them much differently than we do.

Today, we are heading straight into the dark and attempting to light some candles along the way.

If you remember the questions brought up by this series’ previous articles (1, 2), you’ll know we’re interested in learning why and how the ancients built beautiful buildings. We ask this question to determine the larger mystery at hand: what the hell has happened to our own architecture?

To begin to answer today’s question, I intended to bring in the works of three experts. However, the post became so long that I’m going to have to break answering this specific question into an additional article. Today, we’ll study the ideas of the first two:

Mario Baghos, a Catholic PhD Theology Lecturer at Notre Dame Australia, and

Christopher Alexander, the UC Berkeley architect and design theorist whose works we have already depended on thus far.

By the end of examining these two writers’ diverse yet related ideas, we’ll have a better picture, albeit of course incomplete, of what the ancients were up to. And by the time we bring in the third, we might even have an idea of why we’ve gone astray.

Why were ancient cities built as they were?

In his book From the Ancient Near East to Christian Byzantium: Kings, Symbols, and Cities, Baghos goes to great lengths to detail how past cultures, from ancient Mesopotamia — possibly the birthplace of civilization itself — to old Egypt, Greece, Rome, Israel and on up to medieval Christian Byzantium, built their cities as imagines et axes mundi. Or, in layman’s terms, images and centers of the world.1

The concept isn’t as complicated as the Latin terms may imply.

Essentially, the ancient city was built in a location where all three “realms” — heaven, earth, and the underworld — were perceived to have collided (axes mundi, a center). And at this cosmic juncture, the ruler(s) and inhabitants would establish a temple (or some other sacred site) and fill it with religious symbolism through architecture, sculpture, paintings, etc. (imagines mundi, images) to mark the spot.2 Around this spiritual axis point, the rest of the city bloomed.

This process is important to note because of the primacy of the imagines et axes mundi concept for our ancestors. The temples and religious buildings were the focal points around which the other structures in the city oriented themselves.3

Think about what this means. If the city is based around sites of religious importance, then the entire civilization is constructed in such a way as to continually reinforce that culture’s worldview, to tell the story of how humanity relates to and interacts with the cosmos at large.

Put more simply, everyone was consistently pointed toward answering the question: what is the meaning of life?

Which, you know, is a pretty big deal.

I’ll briefly pull a few examples from his book to further illustrate what this actually looked like.

Let’s start with the oldest civilization: Mesopotamia. The Sumerians built step pyramids, called ziggurats, in the center of their cities.4 This religious structure, intended to quite literally link heaven and earth,5 was the beating heart of the city, with all other structures emanating outwards from it. Instead of saying that the Sumerians built “cities,” it may actually be more accurate to refer to them as building “temple-cities,” where the religious nature of the locale is put front and center.6

In ancient Egypt, we find a similar ethos. For example, the cities of Hermopolis, Heliopolis, Thebes, and Memphis, among many others, all claim to be the place from which the rest of the world was created.7 The erection of temples, pyramids, and vertically oriented obelisks — all religiously symbolic structures in nature — formed focal points in their cities and recapitulated the Egyptians’ understanding of the cosmos at large.8

In Greece, the importance of religion in city founding continued its historical trajectory. For example, consider the story of the Palladion. The Palladion was a wooden image supposedly built by the goddess Athena and cast from heaven to earth by the god Zeus. At the point where this object was believed to hit the earth, the Greeks founded a temple, and (it is implied) a city sprung up around it.9 This is just one instance of how the Greeks “believed that the site of a city should be chosen and revealed by the divinity,”10 how the very location of the city itself was determined by religious understanding.

By now you get the point, but bear with me for a few more examples. It’s important to understand that this pattern, that of city creation as an intrinsically religious enterprise, is inherent to city building for nearly all of history.

In Rome, the temple of Vesta is a great example. This structure was circular in form, meant to represent the universe in its entirety, and had a hole in its roof through which the “perpetual fire” billowed.11 The entire structure is a cosmic symbol, linking the earthly realm to the heavenly through the fire’s smoke. Located in the Roman Forum, the temple of Vesta was thus an “imago mundi [image of the world] situated in the centre of the city, [symbolizing] the centrality of Rome to an eternal cosmos….”12

Clearly, the Romans viewed their city as intimately connected to the cosmos and divinity.

Let’s now consider ancient Israel. Many readers will be familiar with Mount Zion, the cosmic mountain of this ancient people. According to Baghos, “the temple—itself an imago mundi—is built on Zion (upon and around which Jerusalem is constituted)”.13 The ancient Israelite’s most important city is built around a mountain crowned with a temple. The imagery here should now be obvious to readers.

And last but not least, the most modern locale Baghos considers is medieval Constantinople. This civilization’s churches are replete with cosmic imagery (think of the domes capping Byzantine churches), and “these churches literally or symbolically constituted the centre of orientation for the inhabitants, that is, axis mundi [centers of the world]. The location of the place of worship as the focal point of the community…continued in the Christian era.”14

In Byzantium, too, inhabitants’ daily lives centered around and were formed by the religious values of the time.

And that’s just a touch of the examples Baghos provides. If we accept this premise — and after reading his book in its entirety, I really think we should — we can rather confidently answer our question of why the ancients built as they did.

To reiterate succinctly, from ancient to medieval times, cities were built predominately as religious centers.15 Ancient people constructed entire cities themselves (and the buildings that make up those cities) as a reflection of their culture’s worldview about the universe and their own relation to that universe. As such, cities were a “medium for the manifestation of the sacred.”16

This is made obvious not only by where they were built, but what they were centered around and filled with, architecturally speaking.

Before reading this book, I knew religion was important to ancient cultures, of course, but I don’t think I truly understood how deep it went. I thought of religion as one aspect of the ancient culture. Like economics. Or art. Or institutions. As one bullet point when studying culture in general, as it was taught to me in my history classes in school.

That is wrong.

Religion was the guiding spirit for everything that culture did, made, and understood. The economics, art, and institutions were formed around the religious understanding, not alongside it.

Knowing that, if you look at today’s style of city-building, you may well find yourself a little bit horrified at what we’ve done… and how we view ourselves.

But more on that later. For now, we progress to answering question #2.

How were ancient cities built as they were?

Book Two of Alexander’s 4-part set enlightens us as to a possible answer to this question: the how. Entitled The Process of Creating Life, Alexander’s book emphasizes two critical principles that allowed ancient and traditional societies to build superior works, that is…buildings and art and structures that come alive, that speak to us and inspire the soul. These concepts are:

Unfolding Wholeness

Structure-Preserving Transformations

Upon first introduction, these terms may sound rather empty and unintelligible, but hang with me. They have the potential to shift the way you view the world entirely.

I’m not being dramatic, because that’s exactly what they did for me.

Unfolding Wholeness

It is a bit of a challenge to adequately sum up Alexander’s concept of unfolding wholeness without getting lost in the weeds — the definition itself relies on other very specific definitions that are not part of common parlance. That said, I’ll do my best to get the idea across, in general terms.

Essentially, unfolding wholeness is the idea that systems, if left to their own devices, evolve in such a way as to enhance and intensify that which came before them.17

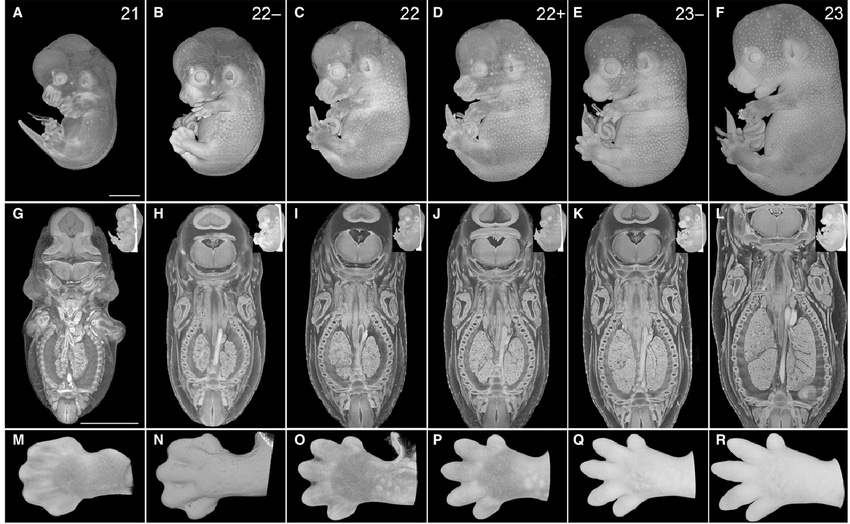

It is very similar to the relationship between DNA and growth. In DNA, all the “code” for the organism is there, but it must be allowed to grow, to unfold to come into its fullest being. Think of an embryo as it develops into a living, breathing baby. Or a seed that becomes a tree. Both of these are prime examples of unfolding wholeness. The life is inherent, built-in, to the thing from the very beginning. And what is there in the beginning gets built upon and intensified in each subsequent stage.

I like his example of the sprouting algae, or the breaking of a wave, both things which we find inherently beautiful.18 In each stage of these events, the second stage always follows smoothly from the first, and so on. Not one stage breaks completely from its predecessor; rather, each subsequent step transforms what was there in the first place in order to enhance it — which makes it even more beautiful.

This is different from “building,” per se. It is not adding one thing to another, like putting Legos together to make a toy robot. It is not A + B. Rather, it is transforming a to A, if that makes sense.

And how can one be sure to enhance, rather than detract from, what was previously given? For Alexander, it starts with recognizing centers in the world. (It is interesting how both Baghos’ and Alexander’s works emphasize the idea of a “center,” is it not? )

What are centers?

From Alexander’s perspective, that’s a very complicated question. But I think of it this way: a center is that which naturally pulls the attention. It is the space that draws what is around it towards itself. And this concept can be applied to every level of reality. From the molecular to the universal, they are all made up of centers. (I know that’s a very quick explanation, but if you want to go deeper into the concept to understand the geometric/scientific explanation, I really encourage you to pick up his first book in the series.)

And while the world is constituted of centers, the centers we find beautiful are (dare I say always?) formed by unfolding wholeness. They are created by a process of enhancement and intensification of what was previously given.

So if we want to create things that fill us with this type of awe, we, too, must aim to enhance the things around us.

Get it?

Structure-Preserving Transformations

Unfolding wholeness is aided by structure-preserving transformations, and thankfully, this concept is a bit more concrete.

The term relates exactly to what you think it does. It means that when any object or process is changed, it is done in a way as to preserve its previous structure as much as possible.19

There is a smooth, relational transition from one state to the next.

Here’s a simple drawing to represent the concept, redrawn by me from Alexander’s own examples in the book.20

And here’s a drawing that shows transformations that do not preserve the original structure.

When speaking about architecture, this concept has one very clear rule:

the system should…do as much as possible to maintain the structure of the wholeness where it occurs, intact, and introduces the minimum new structure which is absolutely necessary, nothing more. The wholeness, then, can be preserved, enhanced, extended, and intensified. It is occasionally pruned and trimmed; and only very rarely destroyed all together."21

In this way, you will preserve the good… and make it better.

Now tell me, do you think we follow this principle when building our own cities?

But I digress.

How do these concepts really apply to a traditional city’s building practices?

So it’s pretty obvious that nature follows the principles of unfolding wholeness and structure-preserving transformations. From the formation of a ripple to the growth of crystals and the evolution of finches, these concepts are clear to any careful observer.

But in human societies of the past, did we, too, follow this pattern?

My favorite example Alexander gives for traditional societies is how Samoans built their canoes.

They would start with a song.

The song would tell them to first find a tree. Then “cut down the tree, strip the branches, hollow the trunk, shape the prow — all the way to the carving of the traditional ornaments which will appear on the canoe.”22

It was a process, not a diagram.

The advantage of a process-based design, rather than a blueprint, is that it allows for reality to give feedback.23

Not all trees are the same size. Not all builders have the same vision. The canoe “becomes unique because of the uniqueness of the tree and of the builder who is making it.”24

Alexander makes the same point with the tipis of the North American Plains Indians, the traditional wall paintings of Mali, a 15th-century Persian rug, traditional Swedish carpentry, Norwegian farm architecture, and entire Austrian villages.25 All follow a process, not a design separated from reality by paper and pen.

This viewpoint change is so critical because it emphasizes one thing: co-creation. Using a process that helps what is already there to become stronger and allows reality to speak back to us as we transform a thing means that we will be creating objects in alignment with the way the universe already works — how we already work.

As a designer myself, this realization was quite shocking… and has absolutely changed my approach to, well, nearly everything.

So what?

With the help of Mario Baghos and Christopher Alexander, I’ve made the case that ancient cities were built by their inhabitants to reflect the universe — and their relation to it — by a process that mimics nature’s own and allows reality to be ever-present in the design.

A verse from the Biblical Genesis comes to mind: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.” And also from 1 Corinthians: “For we are God's fellow workers.”

But have we lost sight of this divine calling?

I think the answer is largely, obviously, emphatically yes. And trying to understand why is where modern neuroscience will come to aid us. But for that, you’ll have to catch the next article. Stay tuned.

Mario Baghos, From the Ancient Near East to Christian Byzantium: Kings, Symbols, and Cities (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022), xii.

Ibid., xv-xvi.

Ibid., 228.

Ibid.

Ibid., 3.

Ibid., 228.

Ibid., 20-21.

Ibid., 30.

Ibid., 47.

Ibid., 51.

Ibid., 67-68.

Ibid., 70.

Ibid., 111.

Ibid., 223.

Ibid., xix.

Ibid., 233

Christopher Alexander, The Nature of Order: The Process of Creating Life (Berkley: The Center for Environmental Structure, 2002), 22.

Ibid., 24, 29.

Ibid., 52.

Ibid., 55.

Ibid., 83.

Ibid., 86.

Ibid., 92.

Ibid., 86.

Ibid., 87-95.

A beautiful article, organic and breathing, recalling the past and formulating it into concepts we can understand. I'm inspired! Looking forward to the next article!

I’m obsessed with, “It is not A + B. Rather, it is transforming a to A”. It has so many implications to design, mathematics, architecture, spiritual understanding, and personal growth. Thank you for writing this! Love it. Keep it up!